Gravitational instanton

In mathematical physics and differential geometry, a gravitational instanton is a four-dimensional complete Riemannian manifold satisfying the vacuum Einstein equations. They are so named because they are analogues in quantum theories of gravity of instantons in Yang–Mills theory. In accordance with this analogy with self-dual Yang–Mills instantons, gravitational instantons are usually assumed to look like four dimensional Euclidean space at large distances, and to have a self-dual Riemann tensor. Mathematically, this means that they are asymptotically locally Euclidean (or perhaps asymptotically locally flat) hyperkähler 4-manifolds, and in this sense, they are special examples of Einstein manifolds. From a physical point of view, a gravitational instanton is a non-singular solution of the vacuum Einstein equations with positive-definite, as opposed to Lorentzian, metric.

There are many possible generalizations of the original conception of a gravitational instanton: for example one can allow gravitational instantons to have a nonzero cosmological constant or a Riemann tensor which is not self-dual. One can also relax the boundary condition that the metric is asymptotically Euclidean.

There are many methods for constructing gravitational instantons, including the Gibbons–Hawking Ansatz, twistor theory, and the hyperkähler quotient construction.

Contents |

Properties

- A four-dimensional Kähler–Einstein manifold has a self-dual Riemann tensor.

- Equivalently, a self-dual gravitational instanton is a four-dimensional complete hyperkähler manifold.

- Gravitational instantons are analogous to self-dual Yang–Mills instantons.

Taxonomy

By specifying the 'boundary conditions', i.e. the asymptotics of the metric 'at infinity' on a noncompact Riemannian manifold, gravitational instantons are divided into a few classes, such as asymptotically locally Euclidean spaces (ALE spaces), asymptotically locally flat spaces (ALF spaces). There also exist ALG spaces whose name is chosen by induction.

Examples

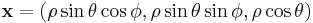

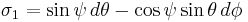

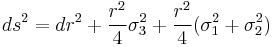

It will be convenient to write the gravitational instanton solutions below using left-invariant 1-forms on the three-sphere S3 (viewed as the group Sp(1) or SU(2)). These can be defined in terms of Euler angles by

Taub–NUT metric

Eguchi–Hanson metric

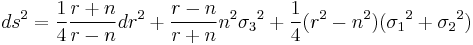

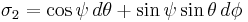

The Eguchi–Hanson space is important in many other contexts of geometry and theoretical physics. Its metric is given by

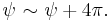

where  . This metric is smooth everywhere if it has no conical singularity at

. This metric is smooth everywhere if it has no conical singularity at  ,

,  . For

. For  this happens if

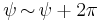

this happens if  has a period of

has a period of  , which gives a flat metric on R4; However for

, which gives a flat metric on R4; However for  this happens if

this happens if  has a period of

has a period of  .

.

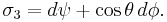

Asymptotically (i.e., in the limit  ) the metric looks like

) the metric looks like

which naively seems as the flat metric on R4. However, for  ,

,  has only half the usual periodicity, as we have seen. Thus the metric is asymptotically R4 with the identification

has only half the usual periodicity, as we have seen. Thus the metric is asymptotically R4 with the identification  , which is a Z2 subgroup of SO(4), the rotation group of R4. Therefore the metric is said to be asymptotically R4/Z2.

, which is a Z2 subgroup of SO(4), the rotation group of R4. Therefore the metric is said to be asymptotically R4/Z2.

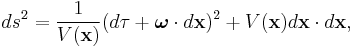

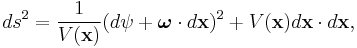

There is a transformation to another coordinate system, in which the metric looks like

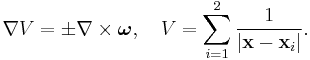

where

- (For a = 0,

, and the new coordinates are defined as follows: one first defines

, and the new coordinates are defined as follows: one first defines  and then parametrizes

and then parametrizes  ,

,  and

and  by the R3 coordinates

by the R3 coordinates  , i.e.

, i.e.  ).

).

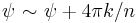

In the new coordinates,  has the usual periodicity

has the usual periodicity

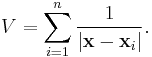

One may replace V by

For some n points  , i = 1, 2..., n. This gives a multi-center Eguchi–Hanson gravitational instanton, which is again smooth everywhere if the angular coordinates have the usual periodicities (to avoid conical singularities). The asymptotic limit (

, i = 1, 2..., n. This gives a multi-center Eguchi–Hanson gravitational instanton, which is again smooth everywhere if the angular coordinates have the usual periodicities (to avoid conical singularities). The asymptotic limit ( ) is equivalent to taking all

) is equivalent to taking all  to zero, and by changing coordinates back to r,

to zero, and by changing coordinates back to r,  and

and  , and redefining

, and redefining  , we get the asymptotic metric

, we get the asymptotic metric

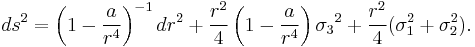

This is R4/Zn = C2/Zn, because it is R4 with the angular coordinate  replaced by

replaced by  , which has the wrong periodicity (

, which has the wrong periodicity ( instead of

instead of  ). In other words, it is R4 identified under

). In other words, it is R4 identified under  , or, equivalnetly, C2 identified under zi ~

, or, equivalnetly, C2 identified under zi ~  zi for i = 1, 2.

zi for i = 1, 2.

To conclude, the multi-center Eguchi–Hanson geometry is a Kähler Ricci flat geometry which is asymptotically C2/Zn. According to Yau's theorem this is the only geometry satisfying these properties. Therefore this is also the geometry of a C2/Zn orbifold in string theory after its conical singularity has been smoothed away by its "blow up" (i.e., deformation) [1].

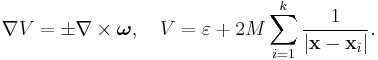

Gibbons–Hawking multi-centre metrics

where

corresponds to multi-Taub–NUT,

corresponds to multi-Taub–NUT,  and

and  is flat space, and

is flat space, and  and

and  is the Eguchi–Hanson solution (in different coordinates).

is the Eguchi–Hanson solution (in different coordinates).

References

- Gibbons, G. W.; Hawking, S. W., Gravitational Multi-instantons. Phys. Lett. B 78 (1978), no. 4, 430–432; see also Classification of gravitational instanton symmetries. Comm. Math. Phys. 66 (1979), no. 3, 291–310.

- Eguchi, Tohru; Hanson, Andrew J., Asymptotically flat selfdual solutions to Euclidean gravity. Phys. Lett. B 74 (1978), no. 3, 249–251; see also Self-dual solutions to Euclidean Gravity. Ann. Physics 120 (1979), no. 1, 82–106 and Gravitational instantons. Gen. Relativity Gravitation 11 (1979), no. 5, 315–320.

- Kronheimer, P. B., The construction of ALE spaces as hyper-Kähler quotients. J. Differential Geom. 29 (1989), no. 3, 665–683.

![ds^2 = dr^2 %2B \frac{r^2}{4} \left({d\psi\over n} %2B \cos \theta \, d\phi\right)^2 %2B \frac{r^2}{4} [(\sigma_1^L)^2 %2B (\sigma_2^L)^2].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/792a2c9a8c926fc9aa7b73eb455ee39f.png)